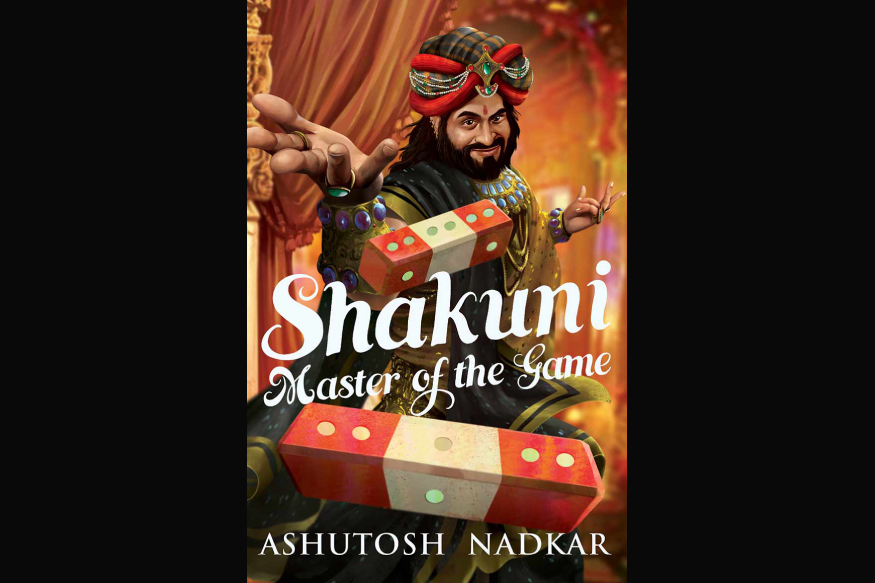

Mahabharata Retold in ‘Shakuni: Master of the Game’

Mahabharata Retold in ‘Shakuni: Master of the Game’on Nov 22, 2019

This re-telling of Mahabharata from the perspective of Shakuni delves into how the heir of Gandhara used the Padavas and the Kauravas as pawns in an intricate and clever power play that culminated in an epic battle of 18 days.

Was Shakuni a villain or victim? In Shakuni: Master of the Game, author Ashutosh Nadkar poses this burning question to the readers. This re-telling of Mahabharata from the perspective of Shakuni delves into how the heir of Gandhara used the Padavas and the Kauravas as pawns in an intricate and clever power play that culminated in an epic battle of 18 days. The following is an excerpt from Ashutosh Nadkar’s book which has been published by Juggernaut. The next day I woke up late in the afternoon. My attendant brought me news so grave that my hair stood on end. Gandhari’s condition was critical. The attendant told me that Queen Gandhari had struck her womb repeatedly to force her body to go into labour. When I reached her room I saw a team of physicians standing around her. My sister lay on the bed, her body pale and deathly cold. Dhritarashtra sat by her bed, his head bent low. Had Gandhari really assaulted her own body? I suspected that Dhritarashtra’s attack on her the night before might have led to this. It is quite possible that Dhritarashtra had hit her harder after I had left the room, leading to Gandhari’s miscarriage. However, the hour demanded swift action, not speculation. The physicians seemed to be giving up on my sister. It was then that Sage Veda Vyasa entered the room. Veda Vyasa had been living in a forest close to Hastinapura. There he had built himself a hut, where he sat and meditated. Not only was he known in our world as a wise sage but also as an expert healer. Dhritarashtra had sent for Veda Vyasa when Gandhari’s condition had worsened. The sage examined Gandhari’s limp body thoroughly and forced a medicated liquid down her throat. He put his hand on Dhritarashtra’s shoulder and assured him that his wife would recover soon. I sighed in relief. Veda Vyasa then examined the blob of flesh that now came out of Gandhari’s womb and said, ‘Sometimes, nature does things that are beyond our ken.’ The sage continued, ‘Many physicians have probably heard of cases where, instead of giving birth to babies, women have pushed out a mass of flesh from their womb, especially during a miscarriage. However, what has come out of Gandhari’s womb looks different to me. This is not just a blob of flesh. This looks to me like a number of fetuses fused together. I can feel the life force throbbing in them.’ I saw a ray of flickering hope and I asked Veda Vyasa, ‘Oh, wise one, can we not miraculously breathe life into them? Can these embryos not evolve into human babies?’ Vidura frowned and replied to me even before the sage could say anything. ‘Have you lost your mind, Prince Shakuni? How can this blob of flesh be given human form?’ Veda Vyasa was also annoyed by Vidura’s intervention. He said, ‘Vidura, while no one questions your knowledge of ethics and politics, there is a vast lacuna when it comes to your knowledge of medicine and science. Prince Shakuni has raised a potent question. However, the answer to that question is not an easy one.’ Then, addressing me, Veda Vyasa said, ‘It is indeed possible to breathe life into this mass of flesh, Prince Shakuni, but that will involve an extremely complex surgical process. We might be able to aid the development of these embryos into human forms using that method. However, I cannot guarantee success.’ By that time the queen mother, Satyavati, the queens Ambika and Ambalika, and Bhishma had assembled in the room. Vidura said to Veda Vyasa, ‘With your kind permission, sir, I would like to ask you a question.’ ‘Do not hesitate to ask me anything, Vidura.’ ‘Wise sage, will these embryos grow into healthy children in the future through this procedure that you wish to perform? Will they be both physically and mentally sound?’ ‘Dear Vidura, I am here today in the capacity of a physician, attending to Dhritarashtra’s and Gandhari’s needs. It is not my place to comment on the future at this point in time. That would be the duty of a soothsayer. As a practitioner of medicine, what I can assure you is that it is quite possible to mould these aborted fetuses into human shape. I cannot claim knowledge of what the future holds. Will the children grow into physically or mentally disabled beings? I cannot predict that. King Dhritarashtra will take the final call on whether I should go ahead with this procedure. The elders of the family are all gathered here. I suggest that you discuss this matter at length but come to a conclusion by dusk. Any further delay will take away the slim chance that we have of giving life to this mass of flesh. If it is too late, I shan’t be able to help you in any way.’ Veda Vyasa left the room. It was evident that Vidura was not in favour of the procedure. Turning to Dhritarashtra, he said, ‘Your Highness, as the chief minister of Hastinapura and your younger brother, it is my duty to advise you that this procedure is not desirable. It is ethically wrong to intervene and reverse a course that has been preordained by nature and the gods. It can lead to dire consequences. Queen Gandhari is out of danger now. We should be grateful for that. And we should forget this miscarriage as a terrible nightmare and move on from here.’ Vidura was known for his understanding of law and ethics. Even someone as wise as Bhishma did not challenge Vidura on these matters. But I could clearly see Vidura’s shrewdness behind his speech on morality and codes of conduct. I would not let him get away with it. I realized that if I did not put my foot down the offering of Gandhari’s precious womb would be rejected as a mass of flesh and thrown away. I said, ‘In principle, I am not against what Vidura has suggested, but I want to remind him that the wisest of wise sages, Veda Vyasa, has pointed out that what has come out of Gandhari’s womb is not merely a blob of discarded flesh but a cluster of fetuses. If we destroy them then we will be committing feticide. That shall amount to sinning. As far as intervening in the ways of nature is concerned, it is my humble suggestion that if breathing life into a fetus through medical intervention is wrong then it must also be wrong to treat the ailing and the diseased.’ Vidura changed his stance and said, ‘Well, even if this is not ethically wrong, the process still remains undesirable because we are uncertain of the consequences that it will yield. Will the children, evolved from these fetuses, be healthy, both physically and mentally? If we suddenly have a lot of crippled babies in this royal household, will that be good for our kingdom?’ I was furious when I heard Vidura’s argument. I wanted to scream out loud and tell Vidura that the man sitting on the throne of Hastinapura was a cripple, as was the man sitting in the forest hiding his impotence behind the cloak of an imagined curse. I held my tongue for the sake of courtesy. Hastinapura had decided to kill my sister’s unborn children. And I stood against Hastinapura. To succeed I would require the support of an extremely influential person. I could not look to Bhishma for help because he would never counter Vidura, no matter what the issue. The only person who could back me, who could fight for the life of those unborn children, was Dhritarashtra. I said, ‘I do not think there is anyone in this room more sagacious than Veda Vyasa. If this process was fundamentally flawed, why would the sage propose it in the first place? In my opinion foeticide is a sin, an extremely grave sin. Does the chief minister disagree with me on this?’ My arguments worked. Vidura could not publicly dismiss the sagacity of the man who had fathered him. However, I knew that I had to make those people see reason and at the same time appeal to the emotions of the stone-hearted, cold, cruel men of the Kuru dynasty. I turned towards Dhritarashtra and addressed him next. ‘Your Highness, you cannot see the physical world with your eyes but you have the gift of vision. You can introspect. The world may reject these fetuses as a mass of flesh but do you not see in that mass a part of yourself? Do you feel nothing in your heart for your own unborn children? My sister is lying there, unconscious, but do you have no feelings whatsoever for the fetuses born from the womb of the woman who has blindfolded herself for your sake? Does it look merely like a blob of tissue to you? Can you not see in it the faces of your sons and daughters? Look. Look hard.’ My eyes were brimming with tears – yes, indeed, there were tears in Shakuni’s eyes, and not hypocrisy or guile, contrary to what the world today believes. I wiped my face and continued to address Dhritarashtra. My words came from the depth of my heart. There was a strange fire in them. I mustered all my strength and anger and thundered at my sister’s husband, the king of Hastinapura. ‘If the members of the Kuru dynasty are afraid of crippled children tainting their family history, then I, Shakuni, prince of Gandhara, pledge to take them away to my own kingdom. I shall be solely responsible for the welfare of those children. I shall bring them up in Gandhara.’ My words touched Dhritarashtra’s heart. He saw me fighting for his unborn children, for their right to live. Despite having fathered them he was in a quandary as to what the right course of action could be. When Dhritarashtra spoke to me, his voice was quivering, but his intentions were resolute. ‘Stop it, Shakuni! Stop it! You have saved me from the grave sin of killing my own children. There shall be no further discussion on this. Send word to Sage Veda Vyasa, request him to get to work as soon as possible. This is not only the plea of a father, but also the command of the king of Hastinapura.’ Dhritarashtra’s voice was now firm. Neither Vidura nor the others present in the room had the courage to challenge him. And that was the second time Vidura had lost to me. Sage Veda Vyasa and his attendants got to work. Dhritarashtra asked me to stay with Veda Vyasa and help him in every way possible. Veda Vyasa managed to separate the mass into a hundred and one fetuses after a while. His pupils sat next to him preparing a paste of different herbs. Veda Vyasa asked me to get small containers for him; he wanted them to be small, closed chambers with just a little hole to allow for passage of air. The sage placed a fetus each in every chamber, which he coated with layers of the herbal paste. He then ordered for the chambers to be placed in a special room, where the temperature would be regulated. Finally he was able to recreate a womb-like space for the one hundred and one fetuses. People looked at the sage in amazement, wondering if his experiment would succeed. Did he really have the power to fashion lives out of a mass of flesh? Veda Vyasa was revered in all of Aryavarta, but especially so in Hastinapura. We took care to follow his instructions to the letter. The moment I had been waiting for with bated breath arrived at long last, and it was time to see the results of Veda Vyasa’s handiwork. The sage had said we would be able to hear the cries of the child in the first chamber before dawn on a particular day. The royal family gathered outside the incubation room that day. I entered the room with some of the sage’s learned disciples. I wanted to be of help to Veda Vyasa and his pupils. It was a cold day and the incessant rain had coloured the skies grey. Veda Vyasa’s students were observing each container minutely. One of them suddenly noticed vibrations in one of the containers. The physicians made arrangements to cut it open, following Veda Vyasa’s instructions. Soon they saw a tiny leg nudging at the walls of the container. Retrieving the baby from that chamber appeared to me like yet another complicated procedure. However, Veda Vyasa’s students, trained as they had been by the wisest of men, successfully managed to bring the baby out without causing it harm. That was a divine experience for me. I saw the child in their arms – a beautiful little baby. One of Veda Vyasa’s pupils bathed the child in medicated water. They then took turns to examine the baby, declared it healthy and handed it over to me. My eyes grew moist. Through my tears I saw the baby’s light brown eyes. The child had managed to dismiss the misgivings of Vidura and all the men of the royal family of Hastinapura. He was a beautiful, healthy boy. Veda Vyasa’s pupils had also certified that. I felt a profound sense of joy as I cuddled the baby in my arms. My love for that tiny bundle of happiness made me forget all the hatred I had for the Kuru dynasty. He made me forget that he was a part of the Kuru family. I rushed out of the room excitedly, eager to take the child to Gandhari and Dhritarashtra. I was surrounded by members of the royal family as soon as I stepped out of the room. Gandhari came rushing to me and almost snatched the baby from my arms, crying tears of inexplicable joy. She kissed the baby repeatedly. Even though Dhritarashtra could not see the face of his son, he caressed the baby over and over again, smiling all the while. There was only one person in the Kuru family whose excitement was feigned and whose face told a different story. The poor chief minister of Hastinapura, Lord Vidura, looked extremely pained and uncomfortable. I was yet to learn how low that man could stoop to further his designs. The birth of Gandhari’s child was no ordinary thing. An extraordinarily learned person like Veda Vyasa had performed some extraordinary feats to give life to an extraordinary child. The fetus that had remained in the mother’s womb for several months and had then grown in a specially designed incubator appeared delightfully extraordinary to us. The baby was much larger than normal babies. His wails were distinctly sharp and emphatic. In fact, he cried so loudly sometimes that the servants were afraid to go near him. Vidura seized that opportunity to build a narrative so vile that the child had to pay for it all his life. Vidura told everyone in the royal family that Dhritarashtra’s son was satanic. His cries were devilish and evil. At an age when most children depended solely on their mother’s milk for nourishment, Dhritarashtra’s son could digest not only vegetarian foods but also meat. These signs were regarded as inauspicious. Vidura talked the astrologers into warning the Kuru family that the newborn child would lead Hastinapura to destruction. Dhritarashtra was advised to give up his child for the welfare of his state. I was completely astounded that a state known for its progressive ways had such little tolerance for anything that was out of the ordinary. The child’s extraordinariness was turned into an axis around which people started playing dirty games, going to the extent of asking the father of the child, the king of the state, to give the baby away. Dhritarashtra, of course, had abandoned all such thoughts the day I had proposed to take on the responsibility of his unborn babies. His child had inspired in him feelings of affection and fatherly tenderness that he had never experienced before. I also saw Dhritarashtra excercising his power for the fi rst time that day by dismissing all the naysayers. But Vidura and his rumours had managed to turn a little baby boy, who could neither walk nor talk, into a villain for the people of Hastinapura.

Book About Shakuni

Shakuni Book

Shakuni Master of the Game

Shakuni Master of the Game Book

Shakuni Master of the Game Book Review

Shakuni Master of the Game Launch

Shakuni Master of the Game Release

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.